“Where are you from, what’s your ancestry?” I get that question a lot and my answer has always been the same. “I was born in Canada, my parents and maternal grandmother in Uganda and my paternal grandparents in India.”

Indian culture was always a big part of my upbringing. My parents enrolled us in Gujarati classes to learn the regional language, we danced and spun at traditional garba folk dance events and we regularly ate meals from the motherland.

But I had never actually been to the birthplace of my ancestors and felt some kind of disconnect even though I had heard so many old family tales about our ancestry.

My maternal grandmother, Radha Raja, born in a tiny village in the Saurashtra region of Gujarat, told my Dad that centuries ago their forefathers had arrived in this Indian state from Sindh, which is now in Pakistan and that prior to that as part of the Lohana Kshatriya warrior class they protected north west territory stretching all the way to Afghanistan against invasions. “The story about our ancestry was passed on to her by her father, who had it passed along by his father,” says my Dad, Subash Chandarana. “They migrated from further north to Sindh and finally reached Gujarat.”

Another story about my ancestry from my parental father’s side, tells of a Rana Natvarsinhji of Porbandar who lived in the Huzoor Palace, a neo-classical masterpiece, perched in all it aging grandeur next to the sparkling Arabian Sea. It`s easy to imagine what the sprawling gardens, now dry and sandy, and the exquisite royal abode must have looked like so long ago. I squinted my eyes in the blistering hot sunlight and admired the crumbling mansion-picturing its cool interior-a treasure box of Art Deco chairs, glittering chandeliers, and oil paintings of Maharajas and Ranis in brassy, baroque-looking frames lining its inner halls. What must my great-grandfather, a simple farmer, have thought if he ever laid eyes on the palace?

After his hunting excursions, Rana Natvarsinhji used to visit my great-grandfather Jadavji Chandarana in his tiny village Bavalvav. The king encouraged Jadavji to send his sons to school and according to my eldest paternal aunt, told Jadavji that the surname Chandarana, which means king of the moon, sounded regal and that his sons looked like princes and should be educated.

Jadavji sent Madhavji and his brothers a few miles down the road to study in the city of Porbandar, birthplace of Mahatma Gandhi. In the early 20th century many Gujaratis from Saurashtra were moving to Africa for better opportunities. Madhavji and his brothers boarded a ship to make the risky journey to Uganda where he found work as a manager at the Mehta Group`s sugarcane company in Lugazi, established by another Gujarati named Nanji Kalidas Mehta.

During their six weeks at sea the ship rocked and lurched. Babies cried. People vomited from nausea. My Dad, who also made this passing several times on the SS Bombay during his studies in Mumbai, tells of handing out cloves to fellow passengers to reduce dizziness.

All of these stories of the past seemed so outrageous in comparison to my simple existence in the Canadian suburbs. And they captured my attention.

But how true were these tales?

Years later, I boarded a plane and finally made the long trip to India hoping to find some answers about my ancestry.

The motherland felt comfortingly familiar and shockingly strange all at once.

In Porbandar, stray dogs barked aggressively and chased after our rickshaw, darting around cows lying in the middle of the dusty roads, not a worry at all of being struck.

Women in brilliant chaniya cholis, flowing skirts with fitted blouses, bedecked with mirrors and weaved patterns, carried baskets of long grass balanced on their heads. Young and old, they all had blue dot tattoos covering their slender arms, cheeks and necks. I wondered if I too would have looked like these women in my past lives. My grandmother had the same markings done when she was a young lady, a traditional sign of beauty still practiced in this region.

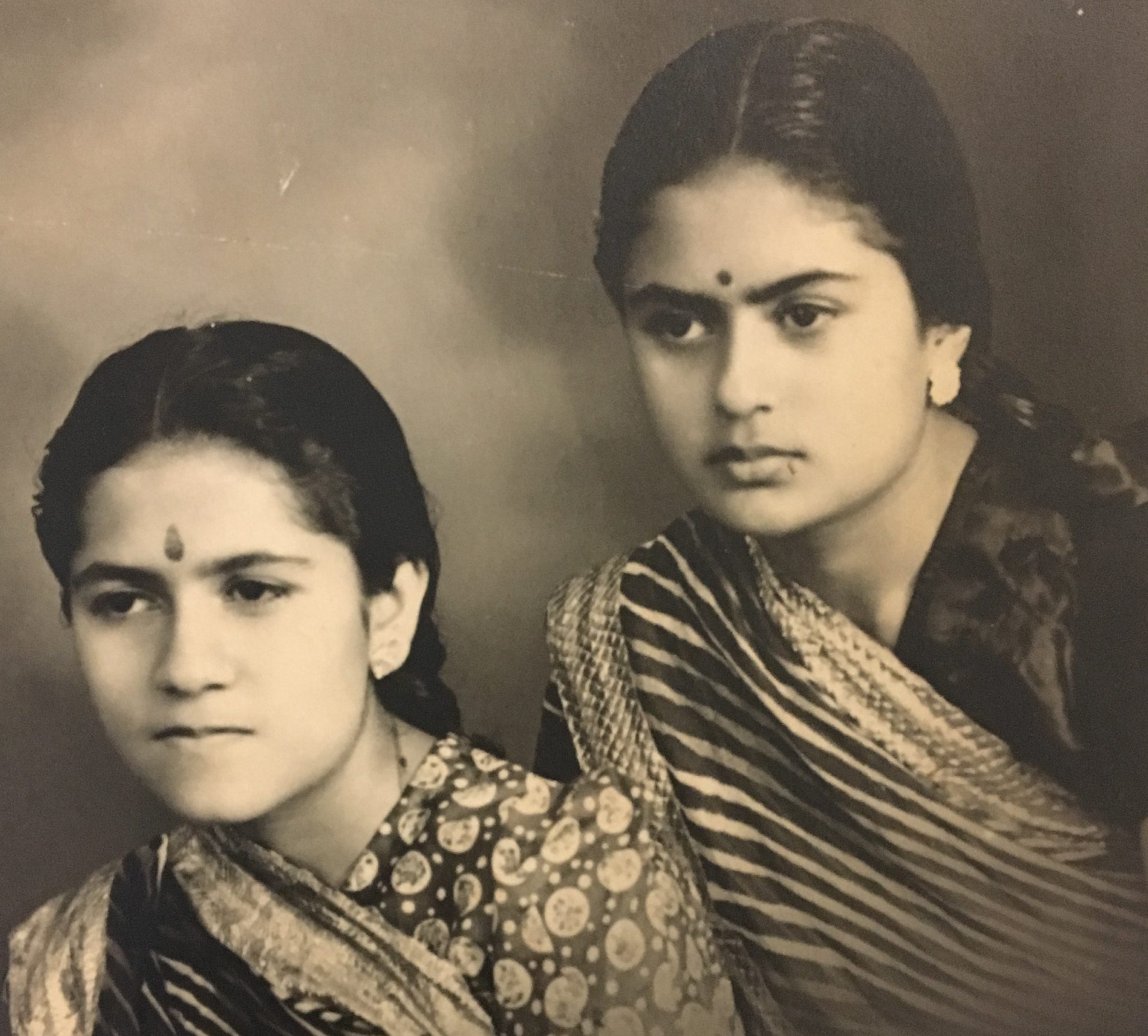

My cousin’s wife greeted us with a delicious meal of daal, spicy cabbage mixed with carrots and fresh rotlis, the same ones my maternal grandmother Sushila Trivedi, rolls so fast, topping the hot puffs with a slab of butter than melts down the sides.

Nani is a bubbly woman whose difficult past has not deterred her from living a cheerful life. Her father, Mohanlal Vyas made the courageous move to Uganda alone as a teenager. Nani was born in Uganda and had her three children, including my Mom, Sadhana, in Kampala.

Every morning, Nani sits by her little mandir, a prayer area, and starts the day with devotion. She wraps on a flower-pattered sari and ties her waist-length grey hair in a bun. The long lines in her earlobes are the markings of the heavy gold jewellry she once wore.

The strong-willed and beautiful women of Saurashtra still wear these heavy baubles and stack bright bracelets on their wrists.

My sister and I had joined our parents on this trip so that our Dad could show us the tiny village where his father was born. Bavalvav is a very quiet place where time has stood still. Small low-level dusty-looking homes seem like they have been there for centuries. Fields of staple plants like moong stretch all the way to rising hills. One of the farmers tells us this was once all Jadavji`s land.

Simple temples beckon believers. Enclosed inside many-a painted image of a regal looking man grasping a curved sword victoriously in the air and riding a white Kathiawari horse (this region is known as Kathiawar). The local saint is Vachradada, revered by farmers to protect their cattle and crops.

It does take some level of faith to endure the many hardships of living in this region. Huge black bats screech as they hang by the hundreds in the lofty trees of the shadowed forest. Cobras slither near the well. Massive, proud peacocks run and suddenly fly into the humid air, their regal blue wings outstretched. A few nights earlier, the locals claim a leopard dragged a sleeping farm worker off into the dark night. Saurashtra is just one of those places that seems to be pulled straight from a page of the Arabian Nights and I was enthralled.

A young farm girl invited me inside her home to drink freshly drawn buffalo milk. She squatted in her simple kitchen and boiled it over an open flame, adding elachi, cardamom and handed me a boiling hot glass of the creamy goodness.

I am happily surprised to learn that once my grandfather safely arrived in Uganda, he sent money back to his village where a school was established and named after his brother Tribhovan who passed away in Africa. Little children, sing the very same Gujarati tune that our Mom sang to us as children. The little girls and boys smile shyly as I admire the golden hoops in their tiny ears.

Although Madhavji Chandarana was a continent away, he never forgot his roots.

I too wanted to be firmly grounded in my identity as a South Asian. Finally, after years of questioning my ancestry, my parents and I took a DNA test with Xcode Life.

The India-based company has launched a global effort called the South Asian Genome Project to expand their South Asian database from 35 ethnic groups to 50.

The results were surprisingly in line with my grandmother’s stories and both my parents’ reports were similar. We are made up of a whole cocktail of cultures and people including the Burusho in northern Pakistan who claim to be descendants of Alexander the Great’s soldiers who allegedly settled in the Hunza Valley; the tribal Brahui people from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran; Velamas from Andhra Pradesh; Russians; Chamars, an untouchable class, who Mahatma Gandhi called Harijans; Afghan Hazaras believed to be descendants of Mongol invader Ghengis Khan; Georgians and traces of Cyprus and Parsi. But the most shocking result was that of the 56 per cent South Asian DNA that makes up who I am today, only 17 per cent of that is Gujarati, while 42 per cent is from Sindh. Although culturally I identify with being Gujarati, my DNA is not so.

The tiny cells in my body tell a bigger story of the cultural interactions and journeys my ancestors must have taken to finally settle in Gujarat. From there they went on to Uganda, where they were uprooted by dictator Idi Amin, fled to London and then immigrated to Toronto in 1977. Even our family’s most recently history attests to human migrations and the mixing of different people.

Near Porbandar’s beach my Dad pointed out to the turquoise expanse. “This is where my father would have climbed into a small row boat taking him out to the larger boat waiting in the deeper water,” explained Dad as tears welled up in his eyes. “His own Dad wouldn’t have even know if his sons made it to Africa alive.”

My sister and I also felt overwhelmed with emotion. It was because of the sacrifices of my maternal and paternal grandparents and my own parents, that we were standing on Gujarat’s coast where my ancestors set out on a new direction so long ago.

As I stood on the shores of the Arabian Sea, glistening in the evening sun, I finally felt like I belonged.

To dig into your family’s ancestry visit Xcode Life.